In northern Italy in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, a good deal of music was composed by women. One of the most productive composers was the noblewoman Isabella Leonarda. She left almost 200 compositions in 20 volumes including mostly sacred vocal music such as motets for soloist and continuo as well as a mass for soloists, choir, strings and continuo. Her only purely instrumental opus is no. 16 which is made up of the 12 sonate da chiesa. These works were used in the celebration of the Catholic Mass.

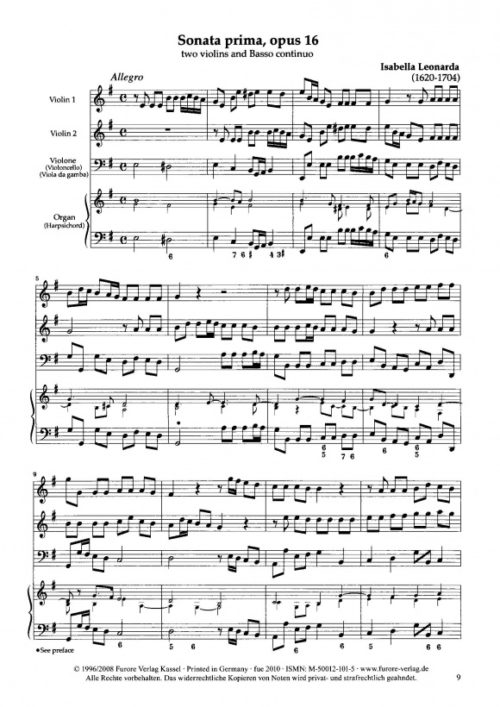

Why did a 73-year-old woman nun and composer, La Sorella Isabella, diverge from her usual compositional habits (the composition of vocal music) and start to write a new kind of music? We will never know, but maybe she was encouraged by the honour accorded to her by the church when she became Madre Vicaria of her convent. The sonatas were written in the same year that she was named to that office. (In the original edition the words Con licenza de Superiori can be found, meaning that the church had permitted these works to be written!)

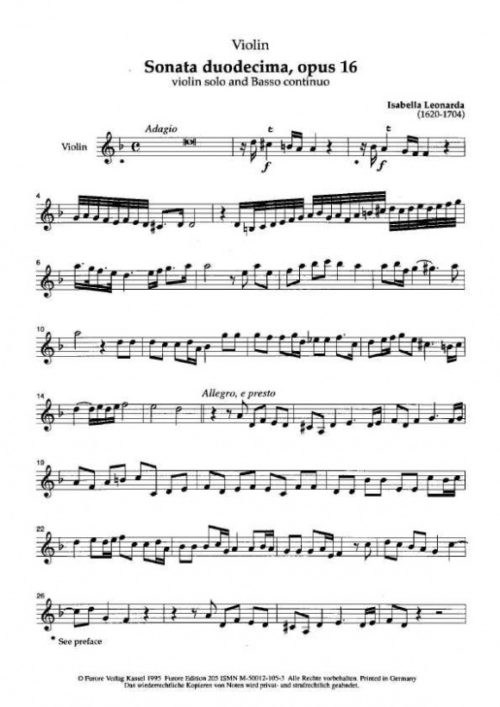

The Opus 16 sonatas are among the first instrumental pieces written by a woman. This fact was probably not known to Isabella Leonarda herself. Perhaps the composer was interested in writing music without texts as a contrast to all her vocal works, or maybe she was just eager to try out the “new” trio sonata style? Compared with contemporary composers (e.g. Corelli) her sonatas are longer, sometimes containing six movements rather than the usual four. She was also more generous than some with modulations, using a large number of related keys within the same sonata.

Leonarda was born on the 6 September, 1620 in Novara and at the age of 16 she entered the convent Collegio di Sant Orsola. In 1686 she became Madre Superior of this convent and in 1693 Madre Vicaria. This convent was closed in 1811. In the 17th century it was a kind of teaching school for girls, the curriculum of which certainly included music. It is not known who taught Leonarda to compose, but in his Dizionario Ricordi della Musica e di Musicisti (Ricordi, Milan, 1959) Sartori makes the assumption that the Maestro di Capella of the Novara Cathedral, Gasparo Casati was her teacher. Her first composition appears in a printed work which he published around 1640. This was a common way for first works of composers to be presented to the public at the time.

The French music lover and collector Sebastien de Brossard (1655-1730) knew Leonarda’s music well and appreciated it especially. This is documented by him in Catalogue des livres de musique theorique et pratique (Paris, 1724).

Considering her large compositional production, Isabella Leonarda has been almost fully ignored by today’s musicians, music students and music scholars. However, given a chance to hear it, many people discover the creative force of her music.

Literature:

Bowers -Tick: Women making music, the Western Art Tradition 1150-1950, MacMillan Press, 1986

Caldwell, J : Editing Early Music, Early Music series 5, Clarendon Press, 1985

Carter, Stewart Arlen: The Music of Isabella Leonarda, Diss. 1982 ,Stanford University

Pendle, K : Women & Music, A History, Indiana University Press, 1991