During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries France produced a number of distinguished musicians, not least among them Elizabeth-Claude Jacquet. Born in Paris in 1665, Elizabeth very early in life achieved fame as a harpsichordist and was engaged to provide musical entertainment at the court of Louis XIV. Her appearances as singer, harpsichordist, and composer elicited high praise and brought her great renown, even in foreign countries. After leaving her royal employ in the early 1680s and marrying the Parisian organist Marin de la Guerre, Elizabeth now Mlle de la Guerre developed a wide following through ongoing activity as a composer and performer. Highlights of her early years in the public sphere included publication in 1687 of her first book of harpsichord pieces and production seven years later of her tragödie lyrique, Cephale et Procris the first composition by a woman to be presented at the Academe Royale de Musique. In the early 1700s, following the deaths of her father, son and husband, La Guerre’s creative activity intensified. In fact, she issued most of her publications between 1707 and 1715. She also inaugurated a series of harpsichord recitals at her home where, until her retirement in 1717, all the great musicians and fine connoisseurs went eagerly to hear her.’ By the time of her death in 1729, La Guerre was considered one of the great artists of her time whose feats as composer and performer merited enduring recognition.

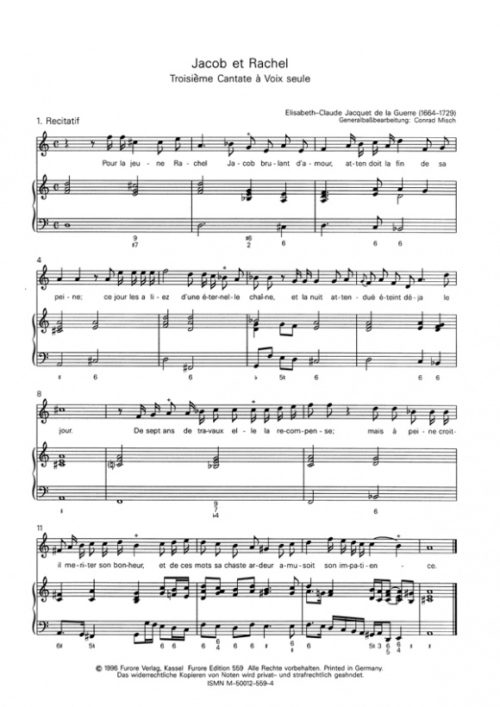

La Guerre’s extant compositions include stage works, popular songs, cantatas, harpsichord pieces, and sonatas a range of production that demonstrates not only her versatility but also her openness to new forms and styles. La Guerre’s sonatas were among the first composed in France. They comprise six unpublished works (two solo sonatas and four trios) that date back to at least 1695, and six Sonates pour le viollon et pour le clavecin published in June of 1707.

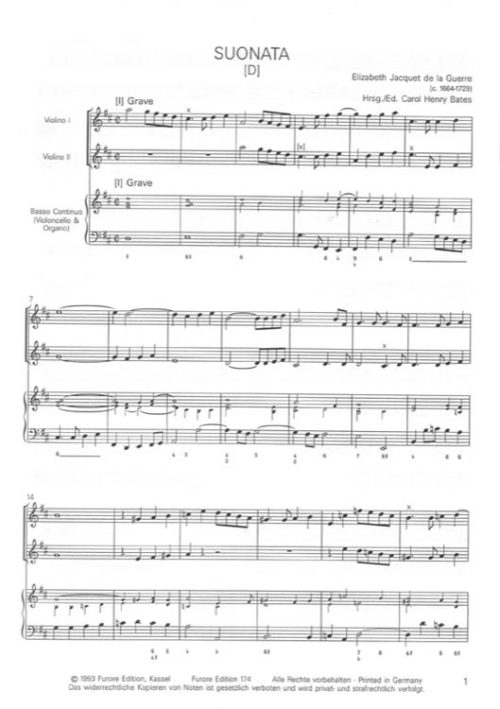

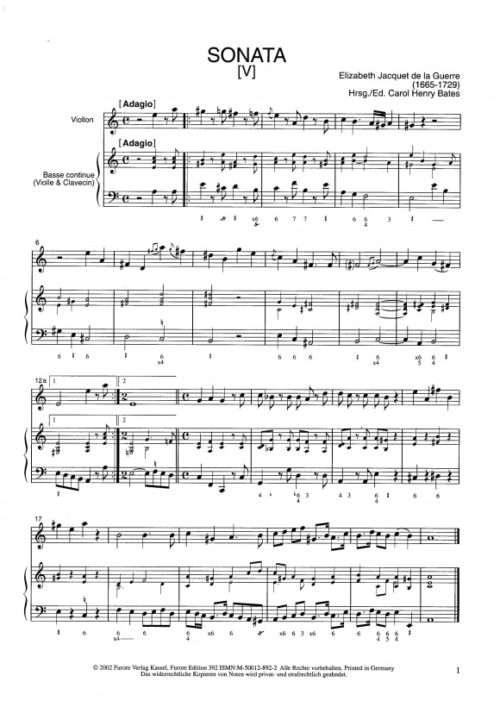

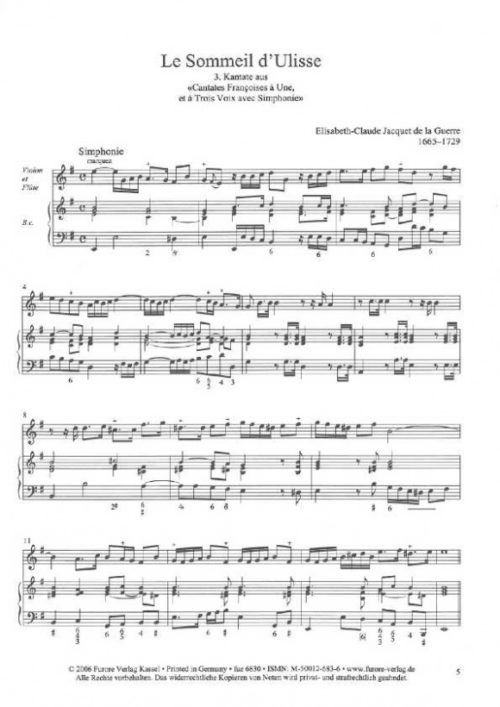

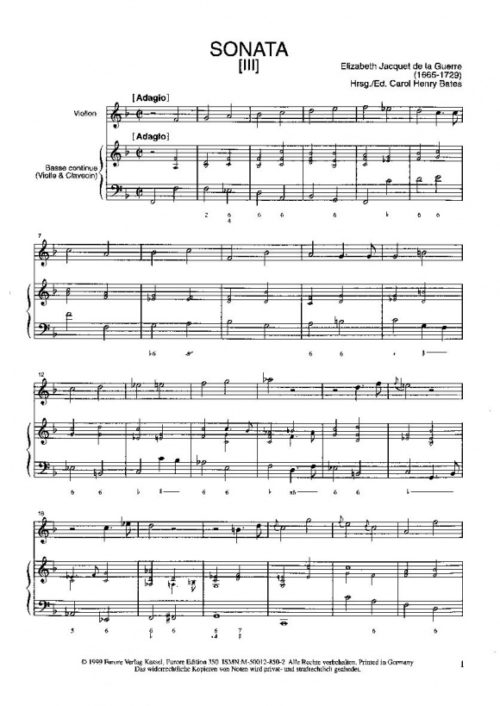

La Guerre’s sonatas as a whole contain four to nine movements arranged on the basis of contrast but without adherence to any one pattern. Movements with tempo titles prevail, but arias and dances are also present. Especially noteworthy is the preponderance of slow finales; eight of the twelve pieces conclude with either an adagio or an aria. The arias are particularly notable for their changes of instrumentation and for their soloistic use of the melodic bass instrument. Although La Guerre’s sonatas display a considerable variety of compositional techniques, they nonetheless exhibit several characteristic features, namely, simple yet artful melodies, repeated-note patterns, syncopations, major-minor inflections, and harmonic mutations. Frequent changes of mode and an occasional incorporation of contrasting keys attest to La Guerre’s love of tonal contrast.

La Guerre’s sonatas of 1707 display freer handling of the violin, increased rhythmic subtlety, and greater expressiveness than do her unpublished works for violin. Interestingly, Sonatas V and VI of 1707 include recastings of portions of her first unpublished solo sonata; these provide valuable insight into the evolution of La Guerre’s compositional techniques.

Carol Henry Bates